WHAT IS A SHARE?

A share is a part ownership of a company. All companies have shares – but the only ones which we are interested in are the ordinary shares of public companies that are listed on the JSE. If you look at the price page of your newspaper, you will see that these companies are grouped into “sectors” and “sub-sectors”, mostly according to the industry that they belong to. Each of these companies has a quantity of “issued shares” – meaning shares which have been sold to members of the public (in the primary market) in exchange for the money needed to start or grow the business. Once those shares are issued (i.e. sold), members of the public can then buy and sell them between themselves (in the secondary market) – and this activity in the secondary market has no direct impact on the company itself.

If the company is perceived to be profitable and growing then the shares will go up, and if not, then they will go down. You should note that this is a “perception” of how well the company will do in the future - in the eyes of the shareholders who may or may not be well-informed, educated and experienced enough to evaluate the company correctly. Even if they are, they will usually have different opinions about what it is worth. Indeed, that is why we have a market – because people have different opinions about the same share on the same day at the same time – one thinks it is going up (the buyer) while the other thinks it is going down (the seller).

WHAT TYPES OF SHARES ARE THERE?

For a company to sell shares to the public it must first obtain authorisation to do so from the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC). Once this permission is obtained, the number of shares which it is authorised to issue becomes known as its "authorised capital" or “authorised shares”. Once the company has this authorisation from the CIPC, it can then offer shares to the public by producing and publishing a prospectus. The requirements for what must be included in a prospectus are set down in the Companies Act (71 of 2008). Then, when the public buys its shares, the number of shares which it has sold in this way becomes known as its "issued shares" or “issued capital”. Usually, companies do not issue all the shares that they are authorised to issue. You can see the company's issued and authorised share capital in your software by clicking the "Current Company Comment" on the top left-hand side of the screen in ShareFriend Pro when you are in the chart of the share that you want to see. Thus, for example, at the time of writing this module, Sasol had 1 127 690 590 authorised shares, but had only issued 626 034 410.

The most common type of share, and the one which we are interested in, is called an “ordinary share” or “equity” share. This type of share benefits if the company makes good profits – and suffers if the company makes losses. In other words, it participates directly in the risks and rewards of the business

PREFERENCE SHARES

These shares get a preferential dividend – which means that they always get their dividend first, before the ordinary shareholders. However, their dividend is limited to a fixed percentage of the share’s “par value” or a fixed number of cents per share (The “par value” of a share is the price for which it was first sold to the public by the company in the “primary market”).

There are quite a few different types of preference shares (“prefs”):

- Cumulative – These preference shares accumulate their dividend if the company is unable to pay them a dividend in any year. If that happens then they get a double dividend the next year and so on. Obviously, this adds to their security. Sometimes cumulative prefs can have a backlog of 7 or 8 years of unpaid dividends – all of which must be paid before the ordinary shareholders can get anything.

- Redeemable – These shares are almost the same as debentures or long-term loans because they are bought back by the company at a future specified date. The difference, of course, is that, being shares, the directors are not obliged to pay dividends while debenture holders must be paid their interest.

- Participating – These prefs participate to some extent in whatever ordinary dividend is paid out to the ordinary shareholders. Thus, for example, they might get one more cent for every ten cents paid out in ordinary dividends.

- Convertible – This type of pref converts to an ordinary share on a specified date in the future. This means that the closer that date comes, the more their price behaves like an ordinary share.

- Voting shares and non-voting shares – sometimes pref shareholders cannot vote at shareholder meetings – which obviously detracts from the value of their shares.

- Variable rate – Variable rate prefs receive a dividend which can vary – usually in line with something like the prime overdraft rate from one of the large commercial banks.

A pref can be cumulative, participating, redeemable and non-voting all in one package. If you look through the Stock Exchange Handbook, it provides details of the capital structure of each listed company. There you will see examples of all the types of prefs mentioned above and some others.

So, preference shareholders are more risk-averse than ordinary shareholders. When the company is not doing so well they will get their fixed dividends first and the ordinary shareholders might get nothing – but when the company is doing well, they still get the same fixed dividend, while there is no limit to what the ordinary shareholders could get. So Prefs are less risky but offer less potential than ordinary shares.

SIZE

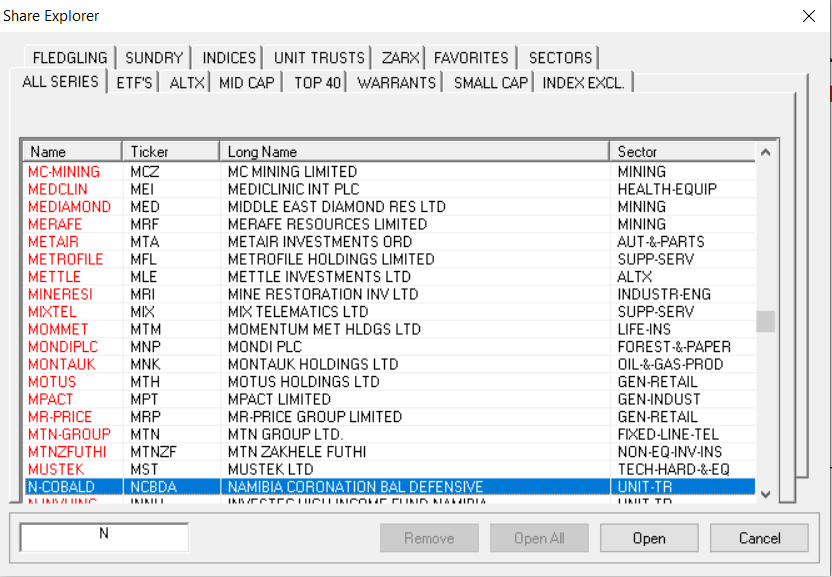

Shares are often classified according to their size. The largest companies which have been profitable for many years, like Standard Bank or Imperial, are known as “blue chips”. Smaller, but nonetheless good growth companies are known as “secondaries” and, finally, the smallest and most newly listed are called “speculative”. These categories are followed to some extent by the major JSE/FTSE indexes. Thus, the JSE’s Top 40 index has the 40 largest companies listed in the JSE Overall index. The mid-cap index includes the next 60 largest shares and the small-cap index includes all the rest. There is also a “fledgling index” which is for very small start-up companies, which are not included in the JSE Overall index and many of which are listed in the Alt-X market. You can view the shares which are in each of these indexes by pressing any letter key in your software. This will bring up the “share explorer”. Look at the tabs at the top of this window and you will find all the different categories of shares, including those which are in the various JSE indexes:

COMMODITY SHARES

Commodity shares are companies which produce and sell a commodity of some sort. The price of these commodities is normally set in international markets far away from South Africa and is out of the control of the producing company. For this reason, commodity companies tend to be considerably riskier than, for example industrial or financial shares. You can imagine how difficult it would be to run a retail business like Pick 'n Pay if you had no control over your selling prices.

Commodity companies are mostly in mining and selling some sort of raw mineral or metal. This usually means that they have the added difficulty of having to deal with powerful union movements which are entrenched in their labour force.

There are some commodity shares on the JSE which are not involved in mining, but which are nonetheless still a commodity – like Sasol, which derives about 60% of its income from oil-related products and Sappi which produces dissolving wood pulp (DWP) and paper products. Consider the chart of Sasol:

Here you can see that the collapse of the oil price, as a result of COVID-19, caused the Sasol share price to fall as low as R21 in March 2020 – and the share only recovered as the oil price recovered.

In general, we advise investors, especially those who are new to the market to stick to financial and industrial shares and to stay away from commodity shares because of their relative volatility.

OTHER INVESTMENTS

KRUGERRANDS

A Krugerrand is one ounce of gold – nothing more and nothing less. It has no “numismatic” value. In other words, it is not a collector’s item and has no rarity value, no matter what the date is on it or whether it is a “proof” krugerrand or not. You should not pay more for it than the current market value of a krugerrand, which is given on the price page of your newspaper every trading day – and, of course, in your software program (just type “KR”).

Are Krugerrands a good investment? The short answer to that question is gold itself is never an investment because it does not give a return. Gold is the most secure asset that there is – and as such it has the lowest return – zero. Krugerrands do not pay any dividends, rent or interest and they do not add 10% to their weight every year. If you are expecting the third world war, then it would make sense to buy Krugerrands. If you think that South Africa is in danger of descending into the sort of economic chaos that currently exists in Zimbabwe then it may make sense to hold, say, 10% of your wealth in Krugerrands. It is an asset of last resort rather than an investment. Most investors who want to invest in gold prefer to buy a gold exchange traded fund (ETF) – because they do not have to worry about the security of their investment, and they can buy or sell it over the internet. Krugerrands have the advantage that they are anonymous and can be easily transported and sold anywhere in the world.

EXCHANGE TRADED FUNDS (ETF)

An ETF consists of an index or a group of securities organised so that they can trade as a single “share”. You can buy and sell ETFs through your stockbroker, just as you can buy and sell shares – and for the same brokerage charge. The benefit for the investor is that they allow you to invest in a broad spread of shares or securities with a relatively small investment and while only paying the dealing costs of buying shares. There are thousands of ETF’s worldwide and there are about 78 listed on the JSE. Here are a few of the older and better-known ones:

- The Satrix 40, which offers an investment into the ALSI 40 index.

- The Satrix Resi provides investment into the top 20 resource shares.

- The Satrix SWIX allows investment into the top 40 shares, but with about half the exposure to resource shares as in the Satrix itself.

- The Itrix enables you to invest in the top 100 shares trading on the London Stock Exchange.

- The Eurostoxx gives you the 50 biggest companies in Europe.

- The Satrix Divi is an investment in those shares from the Alsi 40 which pay the best dividends. It is therefore suitable for people who are looking for a larger income from their investment. It currently enjoys about 4,5% dividend per annum, plus the capital gain in the underlying shares. Like all EFTs it has very low costs (less than 1% per annum).

- Newgold is provided by ABSA bank and consists of a direct investment in gold bullion.

- Newrand is also issued by ABSA and is an investment in the top 10 South African rand hedge shares.

Those mentioned above are just a few of the better-known ones and new ETF’s are listed on a fairly regular basis. To see all ETF listings currently listed on the JSE, you should look in the ETF’s folder located under the ETF’s tab found in the Share Explorer of your software. Alternatively go to https://www.etfsa.co.za/ETFs.htm

The advantage of investing in an ETF is that you then only have to choose a particular market strategy – like investing in rand hedges or in gold bullion or industrials. Your spread of investments is already assured, and your dealing costs are very low. So, ETFs suit the investor who does not want to go to the trouble of stock-picking, and they have the advantage that they are cheaper than unit trusts.

On the downside, you will get the average performance of the sector that you have chosen, rather than the performance of the best share in that sector.

UNIT TRUSTS

Sometimes called a mutual fund, a unit trust is a pooled investment vehicle which invests in a diverse portfolio of assets, including shares, property and bonds, amongst others.

There are hundreds of different unit trusts listed on the JSE covering almost every possible combination of investment. In your software, you can search for a unit trust by typing in "U-" and then the fund name.

Unit trust managers are constantly trying to find new combinations that will appeal to the investing public. A unit trust is set up in terms of the Collective Investment Schemes Control Act (45 of 2002) which governs the way they are run or managed. Basically, unit trusts allow the man-in-the-street to invest a relatively small amount on a monthly basis and accumulate an investment in stocks, bonds or international investments.

Within the unit trust companies there are 3 geographic groups namely:

- Domestic

- Worldwide

- Foreign

When investing in unit trusts you should be aware that they charge a fee which works out to be as much as 6% of the capital invested. In other words, if you bought a general equity fund when the JSE overall index was a certain level and then sold it a year later at the same index level, you would find that it had probably cost you approximately 6%. Or, to put it in another way, your unit trusts must go up by at least 6% before your investment is “in-the-money”. Historically, unit trusts worldwide have tended to under-perform the indexes of the sectors where they compete. In South Africa they have the disadvantage that they are required to keep 5% of their funds in cash – which means that they can only generate a return on the other 95%.

THE FOREX MARKET

The foreign exchange market, also known as the currency market, or FOREX, facilitates the trade of currencies all over the world. It is a non-stop cash market where the banks and other institutions buy and sell foreign currency through brokers. Transactions involve the purchasing of one currency in exchange for another. Foreign currencies are exchanged 24 hours a day across local and global markets, which results in their values decreasing and increasing based upon this movement. This market is considered highly risky as any event in real-time can affect the market, making currency prices, especially in emerging markets, very volatile. Currency futures are usually leveraged 100-fold – which means that a 1% move in the underlying instrument can double or wipe out your investment. Buying currency futures is very similar to putting your money on red or black at the roulette table.

Your software includes end of day snapshot prices of these markets. Simply search by typing C-“ and find the currency you would like to view.

THE DERIVATIVES MARKET

A derivative is a type of security which derives its value from an underlying asset. These underlying assets can include such things as stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates and market indices. The derivative is a contract, which involves two or more parties, and its price fluctuates depending on the value of the underlying asset. They can be traded through an exchange or over the counter. An exchange traded derivative is more regulated and standardised, and therefore less risky. The opposite is true of over the counter derivatives.

There are different types of derivatives. Their type determines their function and how they are applied. For example, certain derivatives are used for hedging, others for speculation. An example would be a South African buying shares in a European company – for this investor there is currency exchange risk as the South African rand is very volatile. To solve this problem and hedge against this, the investor could purchase a currency futures contract, which would lock him into a certain exchange rate for the future sale of his shares.

Types of derivatives include:

Futures

Futures contracts originated in farming because of farmers needing to guarantee a price for their future crop, and food producers needing to lock in a price at which they could be profitable. For example, a wheat farmer might conclude a deal to sell 100 bushels of wheat to a bakery in six months’ time (when he had grown it) at an agreed price. The benefit is that the farmer would then be certain of selling his wheat at a price which would be profitable for him. At the same time the bakery would know that they had a guaranteed supply of wheat at a price which would enable them to make a profit.

A contract like this is called a “forward contract”. Each forward contract is unique and that means that there is little or no secondary market for them. For there to be a secondary market, the contracts need to be standardised. So, a future is a forward contract that has been standardised and trades on an organised exchange. The contracts are standardised for their quantity, quality and delivery date. The delivery dates are the end of each quarter – 31st March, 30th June, 30th September and 31st December. Then the price is the only variable and the contracts can be traded.

In the futures markets of the world, only about 3% of futures contacts are actually delivered. The rest are “closed out”. To close out a futures contract, all you need to do is to buy the opposite side of the same contract. Thus if you have contracted to deliver 100 bushels of wheat on a specific date, you can buy another contract to receive delivery of the same quantity and quality of wheat on the same date – then you can step out of both contracts.

This type of agricultural futures market began in America and specifically in Chicago. Once they were running smoothly for many agricultural products from wheat to frozen orange juice and pork bellies, it became apparent that other non-agricultural intangibles could be traded in this way. This led to the development of “financial futures”.

A financial future is an agreement by one party to “deliver”, for example, the JSE Overall index at a specified level on a future date. Clearly, financial futures contracts cannot be delivered – so 100% of them are closed out by the date when they mature. This means that financial futures are literally a bet on what happens to the underlying instrument. Whoever is right takes money away from whoever is wrong, and the exchange keeps a small percentage for organising the deal.

When you buy a contract in the futures market, you are only required to put down 10% of the cash value of the underlying instrument which you are trading. Thus, you can command a contract for R10 000 worth of Anglo-American share futures with just R1000. This means that if Anglo goes up by 10% you will have effectively doubled your money – but if it goes down by 10% your deposit is gone. This makes futures contracts very risky by comparison to buying shares directly on the JSE.

If you have an “open position” in the futures market you will have to “mark to market” every single trading day. This means that if the contract goes down you will have to put in extra money to make up the shortfall while if it goes up the surplus will be paid into your account the same day.

Options

Options contacts are also a type of derivative contract similar to a future where their value is dependent on an underlying instrument, but with some important differences. An option is a contract which allows you to buy or obligates you to sell a certain quantity of the underlying security on or before a specified date and at a specified price (the “strike price”). Thus there are two types of options a put option which allows you to sell your securities at a specified price before a specified date and a call option which entitles you to buy a certain security at a specified price before a specified date.

Obviously, a person who buys a put option is bearish – they are expecting the price of the underlying instrument to fall so that they can buy it at a lower price before the maturity date. That is how they will make money.

Conversely, the buyer of a call option is bullish and expects the security to rise so that they can make a profit.

Like the futures market, the options market requires you to put down only 10% of the value of the contract that you want to buy – and you have to mark to market every trading day. So, it is also very highly geared.

Derivatives involve many risks, and it is only a good idea for a private investor to consider this type of contract if they are fully aware of the risks, in terms of the underlying asset, the counter party, the price and expiration, and the impacts on their portfolio. We regard derivatives contracts as nothing short of gambling. They certainly cannot be regarded as investments. An investment is where you buy a high-quality share with very good, long-term prospects and then wait for it to generate a good return. Your risk in buying shares is a fraction of what it will be in a derivatives contract. Derivatives will also require that you watch them all the time when you have an open position – otherwise you could lose a great of money very quickly.

Charts of all the various investments discussed in this lecture module are available in your software and you can look at their prices going back many years, even decades.

GLOSSARY TERMS:

Warning: mysqli_num_rows() expects parameter 1 to be mysqli_result, bool given in C:\inetpub\wwwroot\newage\onlinecourse\content\lecture_modules_content.php on line 21

List Of Lecture Modules