The subject of economics is wide and goes deep. It is essentially concerned with the generation, allocation and ownership of scarce resources within a country. Throughout history, since mankind began to live together in communities, the problem of how to allocate resources has existed. It has been resolved in various ways. In South Africa we have what is known as a “mixed capitalist” system in which the private sector creates surpluses which are then taxed by the government to provide various social needs like roads, medical care, energy, old age pensions and many other things. Within that economy our currency is a symbol of the goods and services which we produce. Its strength or weakness depends on how our country is performing. The currency of a country is like the shares of a listed company. If the company is expected to do well and generate good profits, then its shares will rise and vice versa. The same applies to a country. If it is expected to be successful and generate surpluses, then its currency will appreciate against the currencies of other countries.

The objective of this module is simply to sketch the bare outlines of economic activity, and to explain, as simply as possible, a few basic concepts which you will frequently come across in the financial press and which may impact on your investment decisions.

As indicated above, all countries have an economy within which scarce resources are allocated in various ways – usually through the price mechanism and the market forces of supply and demand, but the government plays a major role in this process through its taxation and expenditure as well as through its creation of laws and rules about exactly how economic activity can take place.

Modern economies use a fiat currency (i.e., a currency the value of which is guaranteed by the government rather than inherent in the currency itself) which is managed by a monetary policy committee (MPC). Their management has a direct impact on the level of gross domestic product (GDP) growth and inflation.

In this module we will deal with:

- The Balance of Payments

- The Level of Reserves

- Inflation

- The Business Cycle

- Fiscal Policy

- Monetary Policy

THE BALANCE OF PAYMENTS (BOP)

A country makes many types of payments to other countries.

Amongst other things it pays for imports, does international assistance schemes, pays royalties, insurance and for services. It pays interest and dividends; it repays loans; it makes payments after disinvestment by foreigners and it also pays for investment by South African nationals into other countries.

Similarly, it receives payments for many things – mostly for what it exports.

If there is a shortfall of receipts against payments this shortfall is met from the reserves. If there is a surplus, this surplus is added to the reserves. If the reserves are insufficient to meet the shortfall, then the country must borrow, or sell an asset overseas, in order to increase its receipts.

In a sense, the country’s reserves can be likened to an individual’s bank account. If he spends more than he receives then his balance will go down and vice versa.

The level of reserves affects the level of economic activity (i.e., whether we are in a growth or recession phase) in the country – in other words, the business cycle. To understand this, you need to understand that money is like a commodity – it can be in short supply in which case interest rates (the price of money) will go up and vice versa.

When the reserves are high, the country is liquid (has a loose-money position), and interest rates come down which stimulates economic growth.

Against this, when the reserves are low, interest rates go up, liquidity (the amount of the money in the economy) becomes tight, and economic growth slows down and may even become negative.

When interest rates increase, this immediately puts pressure on the level of economic activity in various ways. For example, increases in the mortgage bond rate reducing the amount of disposable income that the “man-in-the-street’’ has, so he tends to spend less especially if there are several increases in the rates. The effect is cumulative.

Similarly, when interest rates rise companies that have substantial overdraft facilities will immediately feel the pinch as their interest bills increase. They will also begin to cut back, retrenching staff and postponing the decision to buy more heavy equipment, further reducing demand. The point is that changes in interest rates have a far-reaching effect on the economy – and hence on the share market. The level of reserves is a major factor affecting interest rates, because when the reserves are high the economy is usually awash with cash and hence interest rates are inclined to fall.

FACTORS AFFECTING RESERVES

There are three major elements of the Balance of Payments which affect the level of reserves in South Africa:

- The first is the trade account balance or “gap’’ which is the merchandise exports less imports. Despite the fact that gold production has dropped sharply in this country, gold is included as a merchandise export in South Africa, although in most other countries in the world, which do not produce as much gold, it is regarded as a monetary payment. The term “merchandise” in this context refers to the goods and services imported and exported by a country. This is as distinct from monetary payments. Because gold is included in merchandise exports in South Africa, a change in the gold price is soon reflected in the account balance and hence in the reserves. South Africa’s B.O.P. has gradually become less dependent on gold as our manufacturing and non-mining exports increased and gold output declined.

- The second factor is the services account balance. This includes such things as dividends, insurance, and so on - an item which is relatively small, yet not insignificant.

- Thirdly, we have capital flows - which are divided into long–term capital flows and short-term capital flows:

- Long term capital flows are either long-term loans or direct fixed investments, either into South Africa from outside, in which case there is a capital inflow, or by South Africans into countries outside South Africa, in which case there is a capital outflow. It can also happen that foreigners disinvest from South Africa, in which case there is an outflow of a longer-term nature.

- Short-term capital flows consist largely of bank borrowing by companies and, indeed, by banks to finance foreign trade. By making it cheaper to borrow outside South Africa, the government can achieve an inflow of funds and vice versa.

The decision that companies make as to whether to borrow at home or abroad depends on local interest rates - the lower they are, the more attractive it is to borrow at home and vice versa. In reality, South Africa’s interest rates have consistently been much higher than those of her trading partners for many years because of her emerging market status. In the past, the result of this has been considerable over borrowing by South African businesses overseas. During the apartheid era, this has made South Africa vulnerable to political pressure groups pushing for an end to loans to this country which in turn led eventually to the debt moratorium and subsequent collapse of the rand and the Nationalist Party government. Today, no such pressure exists and the only problem with borrowing overseas is that the rand might fall making the repayments much higher.

The combination of the net flow of capital, the services account balance (sometimes also known as “invisibles”) and the trade account balance make up the balance of payments which, in turn, impacts on the level of reserves.

It is important to understand the relationship of the exchange rate and the balance of payments, especially with the trade account. When the rand falls in value relative to the currencies of our major trading partners, then our exports become cheaper overseas, while imports of foreign goods into South Africa become more expensive locally. The result of this is that we tend to sell more of our goods overseas (because they are more competitive) while consuming fewer of the more expensive imported products. This situation generally leads to trade account surplus and can lead to the rand getting stronger. The opposite is also true. So, any weakness of the rand is, to an extent, self-correcting.

At one time the rand was worth US$1,36, it then fell to being worth about $0,33 and today it is worth just under US7c. The result of this rapid decline in the value of the rand has been that South Africa has achieved trade account surpluses against its major trading partners. During the apartheid era, trade account surpluses had to be used to meet substantial outflows on the capital account as we repaid overseas debt, and as investors withdrew money from the country. Today, trade account surpluses are less common mainly because of the general disarray of our mining industry.

Over the last thirty years the US dollar has also declined against leading currencies, especially the Japanese yen. Consider the chart:

The chart of the US$ against the Japanese yen goes back to May 1988 and up to the end of 2020. As you can see there has been a long-term downward trend characterised by falling tops and bottoms.

In 1970, the US dollar was worth 300 yen and by 1990 it had fallen to 160 yen. Today, it has fallen to around 103 yen. Surprisingly, this substantial decline has not been followed by an improvement in American monthly trade account with Japan. Although the monthly trade deficit has dropped, it has not moved into positive territory. The failure to produce a trade surplus in the US, despite the substantial fall in their currency, is something of a mystery. Probably it results from the fact that the US is finding it difficult to compete effectively (i.e., produce the same quality at an equivalent price) with other nations, especially Japan, China and Newly Industrialised Countries (NIC) such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. America’s trade deficit has been offset by massive capital investments from these same Asian countries - which obviously came in via the capital account of the BOP.

It is also important to realise that when the value of a currency falls, foreign investors in the country (i.e., on the capital account) make an immediate capital loss. This makes them keen to remove their funds - hence the history of exchange control in S.A. to prevent wholesale withdrawal of money from the country.

Watch the media for figures relating to the level of reserves and the balance of payments, and if they are not published in your local paper or the paper to which you subscribe for investment purposes, you can get them from the South African Reserve Bank Quarterly bulletin. The December 2020 bulletin is available online as a PDF file at: https://www.resbank.co.za/en/home/publications/publication-detail-pages/quarterly-bulletins/quarterly-bulletin-publications/2020/Full-Quarterly-Bulletin_No_298_December_2020. In Addition to providing you with a host of economic statistics, the bulletin also gives you an authoritative assessment of the state of the economy.

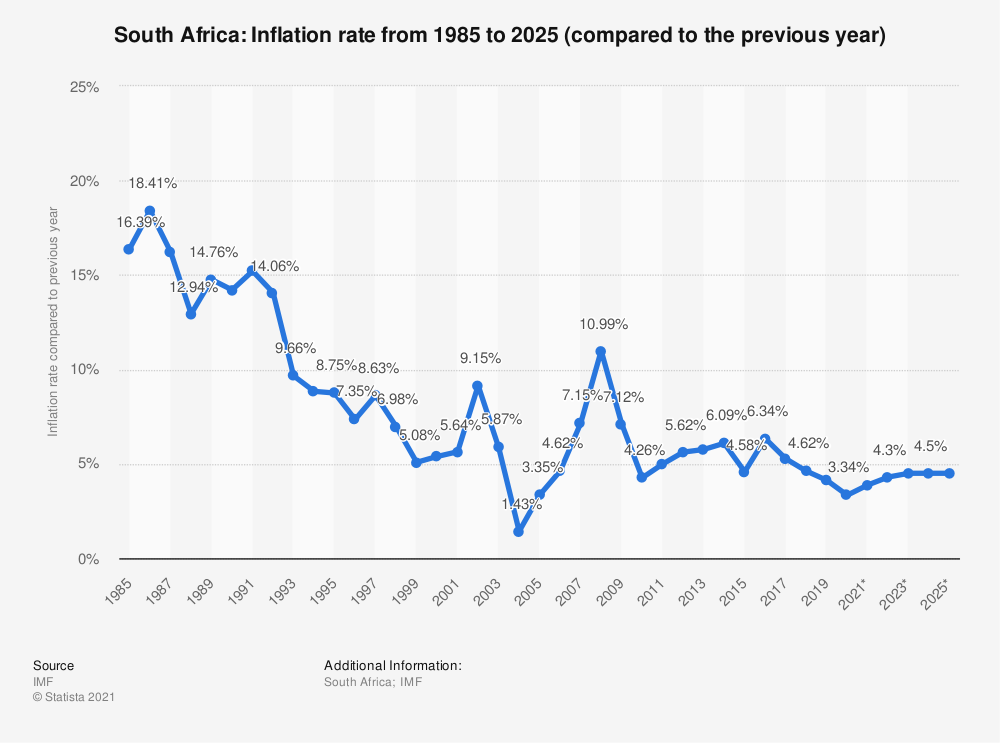

INFLATION

In the past, South Africans became very accustomed to inflation. We had double-digit inflation for more than twenty years, and an entire generation grew up knowing nothing else. More recently, with the introduction of inflation targeting, inflation has come down to below 3%. We regard this as the greatest achievement of the ANC government – that despite the Zuma years and state capture, the ANC maintained monetary discipline and resisted the temptation to print money Zimbabwe-style.

Economists devote much of their time to explaining inflation, and as usual, they tend to disagree between themselves on the essential issues. The explanation which follows is rather simpler, but we feel that, at least over the longer term, it must be correct.

The total money supply of a country (i.e., M3) is really a symbol of the wealth of goods and services that the country produces – rather like the shares of a company which represent the company’s wealth and profitability. If the country is doing badly, then its currency will tend to weaken and vice versa – much as shares do.

With this idea in mind, it becomes clear that, the relative size of the money supply determines the value of that money in purchasing power terms. If the money supply is increased without a commensurate increase in the amount of goods and services produced, then over time, you will have more money chasing the same goods and services and the price of everything must go up. Over the long term, the only institution with the capacity to create money is the government - through the Reserve Bank. If the government creates additional money and spends it on government projects then, over time, the rand in your pocket will go down in value. Essentially, this amounts to a form of taxation - a subtle, usually undisclosed form of tax.

Inflation is not a new idea. In the days of the Roman Empire, the government periodically called in all the coins in the realm (the coins were typically made of gold) on the pretext of re-minting them with the new Caesar’s image. They recorded the details of which coins had been handed in to them by each person. The coins were then melted down and 20% of lead was added. Of course, after re-minting and handing the same number of coins out again, the government was left with 20% of additional coins which they used to finance the next Punic war. In those days, this process was known as “debasement” and today it is called inflation – but it is essentially the same thing!

It is therefore ridiculous for the government to call upon commerce and industry to control inflation - they really have nothing to do with it. Prior to 1994, the government often resorted to creating money to finance its various activities, with the result that there was persistently high inflation. As indicated above, one of the ANC’s greatest achievements is that throughout its tenure, it has been able to keep the inflation rate under control and even reduce it. Government spending has not reduced, however, with the result that it has had to be financed by higher and higher borrowing from the private sector. The state capture activities of the Zuma years have left South Africa with massive government debt that will take many years to repay. The government spending to compensate for the impact of COVID-19 has similarly ramped up the level of government debt.

The share market is a benefactor of high inflation – at least in nominal terms. Shares generally move up in this country during periods of high inflation because they are real assets which makes the share market a reliable mechanism for protecting your wealth against inflation – provided, of course, that you choose the right shares.

But high inflation does a great deal of damage to the economy. In Zimbabwe it has virtually destroyed that economy. It erodes one of the important functions of money – its use as a store of value. During times of high inflation, especially when interest rates are lower than the inflation rate, people have no incentive to save. Indeed, all forms of fixed interest savings actually decline in value – especially after tax. South Africa has a savings rate of less than 1,5 % of income – and that has led to persistently low growth rates in this country. For many years Japan had a savings rate of over 15% - which is the reason for its enormous growth since World War II.

Inflation harms the economy in other ways. It badly affects anyone who has a fixed income or whose income is dependent on interest rates. This affects retired and elderly people who cannot supplement their income by earning a salary.

Inflation also means that the amount of a tax being paid by taxpayers is steadily increasing, because taxpayers are forced into higher and higher tax brackets as the currency loses its value and they need to earn more in nominal terms to stay in the same place. This phenomenon is known as “bracket creep” or “fiscal drag” and it has led to the salary-earners in South Africa paying a disproportionately large percentage of the total tax bill.

There are many other adverse effects of inflation which damage the economy in various ways. The important thing is to understand what is happening and how to protect your wealth against it.

THE BUSINESS CYCLE

When considering the business cycle, it is important to understand that South Africa’s economy is a very small economy in world terms, and it is strongly influenced by the progress of other world economies – especially key trading partners like Europe, America and China. As an emerging economy it is also continuously subject to perceptions of political risk. Being highly dependent on foreign direct investment (FDI), the opinions of overseas investors about the stability of our political institutions are critical.

The alternation between “risk-on” and “risk-off” sentiment internationally has a direct impact on this country. When overseas investors are going through a period of “risk-off” sentiment, it means that they have become risk-averse and are withdrawing funds from emerging markets like South Africa to place them in more secure assets such as US treasury bills (T-bills) and gold. The opposite is also true because secure assets like US treasury bills and gold have little or no return. In fact, the return on the US 10-year government bond is often below 1% while their inflation rate is usually above 1% - which means that US T-bills have a negative real return. The moment investors feel more secure they rush to find investments which offer a strong positive real return. The alternation between risk-on and risk-off directly impacts on the strength of the rand and on our stock and bond markets in this country.

The Zuma years of Gupta influence and state capture were perceived as highly negative by overseas investors with the result that funds generally left the country resulting in a weakening of our currency, especially against first world currencies. It will probably take a decade to recover from the endemic corruption and debt which the Ramaphosa administration was left with. There are some early signs that the steady replacement of corrupt officials as well as their pursuit at law is beginning to have some effect, but the damage is at every level of government and it will take many years to correct. Probably the worst of this is in the massive inefficiency and indebtedness of Eskom and much will depend on how this is handled going forward. The appointment of Andre de Ruyter as CEO of Eskom is beginning to have a positive impact on its performance.

The South African economy has very high official levels of unemployment (variously estimated at around 30%) which have been made worse by the lockdowns and COVID-19. However, it is very difficult to measure unemployment in the informal sector which has become a very substantial employer in the economy. This problem is compounded by continuous illegal immigration into the country from other African countries. The impact of unemployment statistics in South Africa is therefore difficult to assess from an economic perspective. It is worth considering that the informal sector is substantially a euphemism for tax evasion. It is true that the South African tax base has been shrinking with fewer and fewer taxpayers supporting a growing informal sector.

What follows is a description of the normal progress of the business cycle in an “average” economy. These rules and relationships do not often apply in South Africa because of the powerful forces mentioned above, but they are worth understanding and considering.

THE CYCLE

We said earlier that, when the country’s reserves are high, interest rates tend to come down and economic growth results. Conversely, when a country’s reserves are low, interest rates go up, liquidity (the money supply) becomes tight and economic growth slows down as people and businesses pay more interest.

The alternation of these two conditions is called the business cycle.

The business cycle is also normally influenced by the level of indebtedness among consumers and companies. When consumers are taking on more credit (typically as a result of low interest rates) and spending more the economy will tend to do well. Conversely, when they have to repay that debt, they have to spend less and then the economy will slow down.

It is important for you as an investor to become aware of when a change in the direction of this cycle is taking place and indeed, to start anticipating such changes.

The business cycle is a slow-moving thing and, if you are observant, you will pick up lots of indications of an impending change in trend before it actually happens.

However, other investors also tend to perceive these indications quite quickly – and an impending change in the economy from growth to recession or vice versa is likely to result in a meaningful move in the share market, well before the change in the economy actually takes place.

It is often said that the night is darkest just before dawn – so look for signs of the most intense dark.

INDICATIONS OF BUSINESS CYCLE CHANGES

The unemployment rate is a good indication of the progress of the business cycle. While the unemployment rates in South Africa are not reliable in absolute terms, they are a good indication in relative terms. If the official unemployment is rising then the recession is still in progress, but when it begins to improve, it is an indication that businesses are hiring again because they anticipate rising demand for their products. Look out for headlines about redundancies, mass-retrenchments, the “brain-drain”, the shortage of skilled manpower and so on. When the “brain-drain” and redundancies are at their worst, the economy is probably starting to get close to the bottom of the cycle.

You can check this against the direction of interest rates which will typically be going up when the economy is near the top and coming down when the economy is near its bottom.

A further check is the way the market reacts to news. In an expanding economy everything is rosy, and everybody is bullish. The opposite is also true. If the news is universally bad and people are depressed, then you are probably still in a downward phase.

Look around to see the building activity in your area. Are people building new factories and shopping centres? Developers of major construction projects have to have optimism about the long-term future of the economy. Thus, the Mall of Africa and the extensions to the Fourways Mall in Gauteng are an indication of bullish sentiment.

Investors in the share market tend to react more optimistically to news when they are in a bull phase than when they are in a bear phase. If you see worse-than-expected company results coming out and the share price hardly moving down, then you know that you are either in, or nearly in, a bull market. Most of the bad news is probably already discounted into the share price.

Another factor to watch is the level of bad debts, which tends to reach a peak when the economy is at its lowest, as do insolvencies.

Shops become empty of customers during a recession and when you really start to notice a lot of empty shops, then the recession is probably near its bottom.

One measure used by some analysts is the length of retailer summer or winter sales. Particularly long sales tend to indicate an overstocked position – a sign of the beginning of a recession. A slightly shorter sale coming later than usual indicates that the stock levels have come down, and that the retailer is ready for an upturn.

Similarly, you might look at the level of advertising that you come across. Advertising is one of the expenses that companies are reluctant to cut during a recession. In fact, retailers like Pick in Pay and Shoprite will actually tend to increase special offers and advertising when their sales are under pressure.

So much then for measuring the economy by eye and measuring the economy by reference to the reserves.

There is another large body of economics which deals with the Reserve Bank’s actions in stimulating or suppressing economic growth.

This policy falls under two main headings - fiscal and monetary policy.

FISCAL POLICY

Fiscal policy is concerned with the budget and the degree to which the government stimulates the economy by increased expenditure and with higher or lower taxation rates.

The budget is tabled in parliament twice a year, at the end of February and October by the Minister of Finance. In the budget the Minister sets out the projected income and expenditure of the state together with the additional finance that will be required to realise that forecast over the next three years. The budget deficit is the accumulated debt of the government which results from a shortfall of income over expenditure. This is usually expressed as a percentage of the country’s annual gross domestic product (GDP). For example, the Minister of Finance, Tito Mboweni in his mid-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) in October 2020 said that the deficit would rise close to 100% of GDP during the next three years.

If the government debt is very high, then it means that a greater percentage of the government’s income will have to be spent to service that debt and less will be available for other projects. At the time that the ANC took power in 1994, the government debt was excessively high and one fifth of the tax collected was being used to pay interest on that debt. The Minister of Finance, Trevor Manuel, reduced that debt to just 20% of GDP over the next 14 years. When he left office, the debt began to creep up again. Under the tenure of Jacob Zuma and as a result of state capture it is now estimated that the deficit could rise to as much as 80% of GDP over the next ten years. With the cost of COVID-19. the cost of servicing the budget is again expected to rise to about 20% of total government revenue. The size of the government’s debt is of critical interest to international ratings agencies like Fitch, Moody’s and Standard & Poors. In 2020 the last of those agencies, Moody’s, downgraded South African debt to junk status. It will probably take several years before we can again hope to regain our investment grade rating.

Under normal circumstances, a country can choose to increase government expenditure to stimulate the economy in the short-term. The government has been trying to do this with various measures to counter the impact of the COVID-19 lockdowns. Conversely, lower expenditure or higher taxation will tend to depress the economy. Higher expenditure, paid for by higher taxes, will probably have little or no effect – because it is like giving with one hand and taking away with the other.

When new money comes into the economy it has a far greater effect on total income than you might think. This is because of what economists call the “multiplier” effect. Assuming a savings rate of 5%, if R1m of new money is injected, say, into a road contractor to build a road, the road contractor will likely spend 95% of it and save 5%. The R950 000 that he spends then becomes income in the hands of other people in the economy – who will, in turn spend 95% and save 5% of that. Theoretically, this process continues until all the money is eventually saved in one way or another. This means that the effect of that initial R1m injection on the country’s income will be R20m – or the reciprocal of the savings rate. Economists say that the total effect on the nation’s income will be reciprocal of the “propensity to save”. So, if we, as a nation, are in the habit of saving one twentieth of our gross income, then any money into the economy will increase total income twenty-fold. It is important to realise that this effect will also work in reverse when wealth is withdrawn. Sadly, South Africa’s saving rate is far lower than 5% and a major cause of our relatively bad GDP growth rates.

The government should only use fiscal policies to reduce the effect of extreme swings of the business pendulum. If they do, they will influence the timing of the change, but not cause the change itself. Continued high levels of government expenditure can cause a boom to continue beyond its normal turning point.

Although there might be some merit in this of sort stimulation in the short-term, if it continues for too long it may result in inflation.

You should also be aware of the possibility that there is a difference between what the authorities say and what they do. For example, former President Zuma promised for years to undertake massive spending on infrastructure but never put this into effect - which led to the demise of the construction industry.

MONETARY POLICY

Monetary policy is administered by the Central or Reserve Bank though the monetary policy committee (MPC). It concerns the amount of the money in the economy and hence the level of interest rates, and the exchange rate. The MPC consists of 7 members – the Reserve Bank Governor, the 3 deputy-governors and 3 other senior staff members from the Reserve Bank.

In February 2000, the Reserve Bank introduced inflation-targeting as a policy. In terms of this policy, the MPC endeavours to keep the consumer price index excluding mortgage rates (CPI-X) between 3% and 6%. Over the subsequent years the MPC has been very successful in getting inflation down to and even below the lower point of this range.

The MPC meets every two months under normal circumstances but can meet more frequently if required. Each meeting decides after two days of debate whether to increase rates, reduce them or keep them at the same level. After the meeting, the Governor issues a statement in which he summarises the conclusions of the meeting.

Interest rates are the cost price of money.

With this in mind, you can regard the money market like any other market – if money is in short supply interest rates will tend to be high and vice versa.

The South African Reserve Bank, directly and indirectly, through the banks, can increase or decrease the supply of money.

A higher level of lending by the banks causes an increase in the supply of money, and with an increased supply of money one would expect a higher value of transactions to take place in the economy, and therefore a higher level of economic activity. However, a higher level of activity in the economy tends to result in a higher level of imports and lower level of exports, with the result that, in time, the reserves start to run down.

Interest rates are your pointers to watch for future monetary policy, on the basis that when interest rates are high, the monetary authorities are likely to soon take some fiscal action which will slow down the economy, whereas when interest rates are relatively low, the authorities are likely to act to re-stimulate the economy.

With advent of COVID-19, the MPC reduced the level of interest rates by 3% to very low levels. They were able to do this because, for all the economic mismanagement in South Africa during the Zuma era, the country has one of the lowest inflation rates among emerging economies. This has given rise to the suggestion that we engage in “quantitative easing” which is the creation of money by the Reserve Bank with the objective of stimulating the economy. So far, the Reserve Bank has resisted this, probably because of the “moral hazard” that comes with it. After all we have the example of Zimbabwe which literally printed its currency out of existence.

Clearly, monetary and fiscal policy should act in unison, and it is probably only when you start to get a change of trend in both policies that you can start to anticipate the change in trend in the stock market. If monetary and fiscal policy are not coordinated, then the result is usually inflation.

THE INFLUENCE OF POLITICS ON THE ECONOMY

So far, we have only dealt with the effect of economic factors such as the level of interest rates, the balance of payments, inflation, and the business cycle. The political situation in the country also can have a strong influence on the share market and the economy. There are essentially two types of political influences.

- The long-term political scenario which embodies the level of perceived risk in the country. In South Africa, despite reforms process, there is still a considerable amount of political risk. This does not affect South African investors unless they have funds outside the country, but it does influence the level of overseas participation in our markets. The arrest of Ace Magashule, secretary-general of the ANC, in late 2020 precipitated a crisis within the ruling party which has still to be resolved. This had a dual impact on the rand because of fears of a more serious split in the ANC countered by optimism about progress in the fight against corruption.

- Short term effects caused by sudden changes in perception of the political future. These normally take the form of a reaction statement made by a political figure. For example, when F. W. de Klerk announced the unbanning of the ANC and the release of Nelson Mandela, our market rose strongly on the perception that international isolation would end and the JSE would be re-rated more into line with overseas markets. Clearly, anything which endangers President Ramaphosa’s position is seen by overseas investors as negative – and vice versa. Going back in history, when Nelson Mandela first indicated that the ANC would engage on a policy of the nationalisation of the key industries, the share market fell heavily as perceptions of a strong economy evaporated, while the appointment of Andre de Ruyter as CEO of Eskom in December 2019 was seen to be positive.

Political events also affect the international markets. When a Republican president loses office to a Democrat, the Dow usually falls and vice versa. This has not been true with the replacement of Donald Trump by Joe Biden – because markets generally did not like the unpredictable nature of Trump’s administration. When Jimmy Carter lost office, the Dow strengthened, and gold weakened. At one point it was rumoured that Ronald Reagan had been assassinated and the gold price rose. These influences of politics on the level of markets tend to be temporary, however, and should not affect your analysis except in the short term.

GLOSSARY TERMS:

Warning: mysqli_num_rows() expects parameter 1 to be mysqli_result, bool given in C:\inetpub\wwwroot\newage\onlinecourse\content\lecture_modules_content.php on line 21

List Of Lecture Modules